The decision to structure an organisation as a non-profit or for-profit is one of the most fundamental dilemmas when launching an initiative, particularly one focused on education in Afghanistan. For me, this choice has been a complex balancing act between financial sustainability, mission alignment, and operational flexibility.

Non-profits have the undeniable advantage of being eligible for international funding sources. Organisations like UNICEF, UNESCO, and other INGOs often open doors to grants, resources, and partnerships. However, these opportunities often come with strings attached—rigid Request for Proposals (RFPs) that dictate the agenda, outcomes, and even methodologies. This predetermined framework can clash with the mission and vision of an independent institution. For example, I envision an educational model where trainee teachers are paid a salary, inspired by Singapore’s National Institute of Education (NIE). Education, to me, is not a project with an expiration date; it is a necessity, the bedrock of a nation’s development. A non-profit model that chases external funding risks becoming project-driven rather than mission-driven.

At the same time, the constraints of a non-profit model raise questions about the scope of activities I can pursue. Some Afghan colleagues have suggested that, because my institution (Kabul Institute of Teacher Education) includes “teacher education” in its name, its activities might be narrowly confined to this domain. They are concerned with the legal constraints and its constitution after registering with the Ministry of Economy.

Those concerns are valid, of course. But education is not limited to classrooms for children. Can I not conduct professional development workshops for corporate teams? Can I not lecture at universities or consult for organisations? These activities diversify income streams, extend the impact of the institution, and reinforce its sustainability—yet they seem at odds with the traditional non-profit framework.

On the other hand, for-profit models offer operational flexibility and self-reliance. With a clear revenue stream, my institution could reinvest profits into expanding its scope, increasing teacher stipends, and enhancing educational quality. However, in a context like Afghanistan, where the education sector is already underfunded, a for-profit model may alienate stakeholders who expect education to be accessible, equitable, and public-spirited. The stigma of “profit-making” could deter potential partners, funders, and beneficiaries.

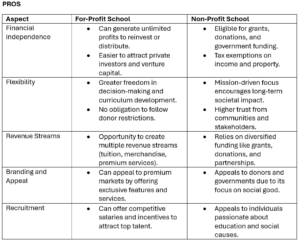

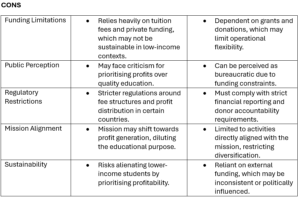

To clarify some of these conflicting thoughts, I turned to Generative AI to help me examine the pros and cons:

This crossroads leaves me wondering if a hybrid approach is possible. Can we create a social enterprise that combines the mission-driven focus of a non-profit with the self-sustaining strategies of a for-profit? Can we have a model where donor funding supports foundational costs while fee-based services—such as corporate training or university lectures—generate supplementary income?

I went back to the drawing board. If I were to quit my job at the university in Singapore and start a small institute in Afghanistan, then it has to be fueled by my true "calling". I shouldn't let money be the only lens to operationalise my vision, though I cannot deny that my vision needs money to be operationalised. After checking with my Afghan counterparts and realising that the concept of a "social enterprise" does not exist in their constitution, it is clear that I can't use that nomenclature.

Ultimately, the challenge for me is not just about choosing a structure but about ensuring that the institution remains true to its purpose: redefining teacher education in Afghanistan. Whether for profit or non-profit, I still want the goal to remain the same—to build an educational ecosystem where teaching is incentivised, valued, and transformative.

After much consideration and alignment to my own personal ethos, I have decided that it would be a non-profit!

Yet new questions arise from my Singapore counterparts. "If I donate to your cause, how can I get tax exemption?", or "Is the NGO registered under Singapore's Charities Act?" If I were to register the NGO in Singapore, it would likely be classified as an International NGO (INGO) under the Afghan constitution. This, however, defeats the purpose. I want the institute to operate at a local level — rooted in Afghanistan, serving Afghan communities, and eventually led by Afghan teachers.

This would mean starting a local bank account in Afghanistan. But with current limitations on international money transfers, would global donations even be possible, or feasible?

I suppose I will find out when the time comes to cross that bridge.